ELECTION CORRUPTION: Palm Beach County Taxpayers Funding Wendy Link's Personal Legal Defense

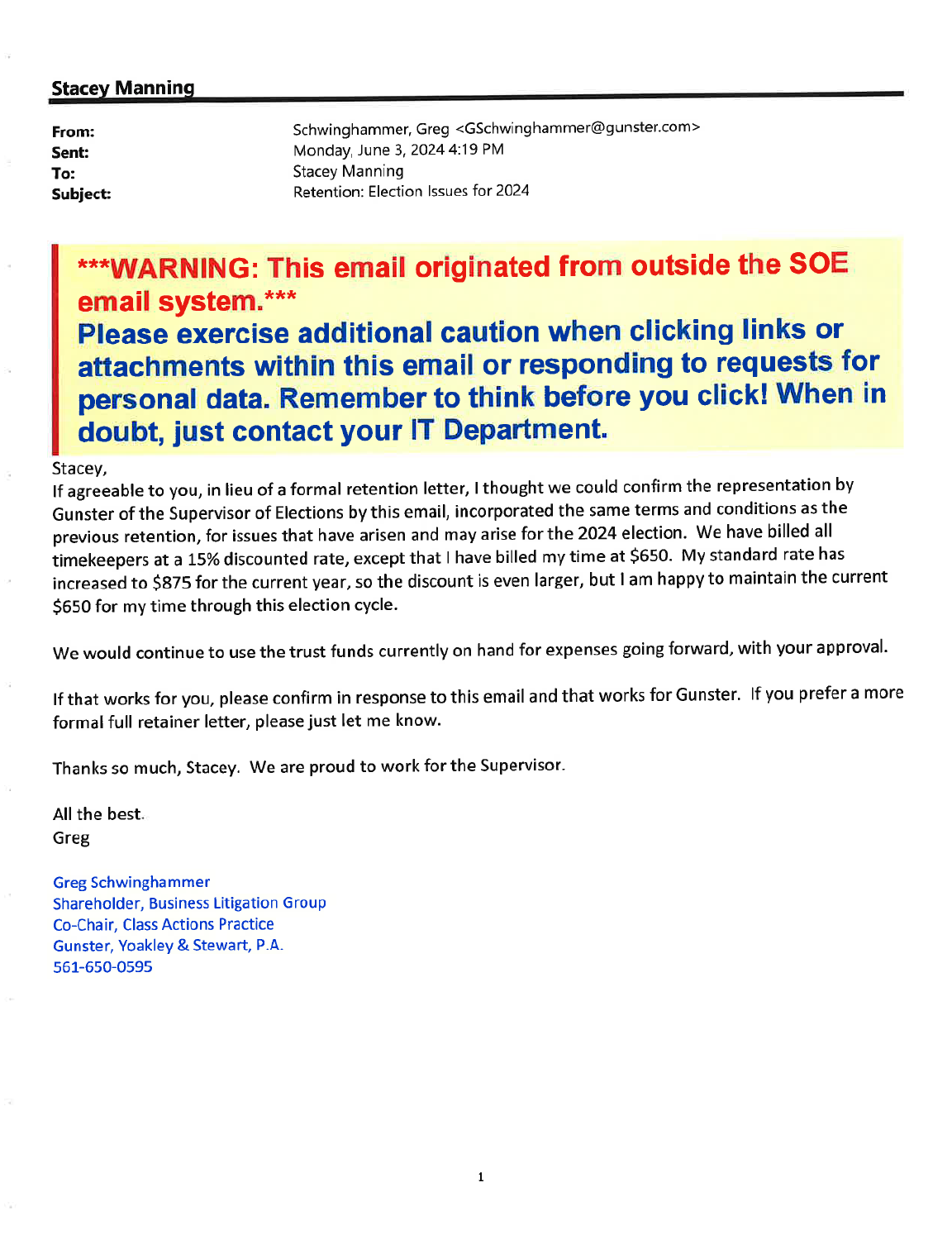

Is this legal? The $650 per hour attorney representing her thinks so... He discounted his rate from $875 per hour. What a bargain...

Is the use of taxpayer funds to defend bad faith activities outside the scope of official duties by public officials legal?

Palm Beach County Supervisor of Elections Wendy Link is getting the very best defense that Palm Beach taxpayers can afford, in direct violation of Florida Statute 111.07, which prohibits the use of taxpayer money for legal fees.

Why is this happening?

FREE FAIR AND TRANSPARENT ELECTIONS…. ARE IN THE PUBLIC INTEREST

Stacey Manning from the Palm Beach County Supervisor of Elections thought this

Why Wendy Link’s Use of Taxpayer Funds for Election Challenge Defense is Illegal

Wendy Link, as a public official, cannot legally use taxpayer funds to defend an election challenge lawsuit, as this action violates Florida law, constitutes official misconduct, and contradicts longstanding Florida Attorney General opinions and court rulings, including AGO 89-77 and AGO 77-87 . This article examines why such expenditure is impermissible, drawing on section 111.07 F.S., the two-prong test from case law, and relevant legal precedents.

Section 111.07 F.S. authorizes public entities to use taxpayer funds to defend public officials in civil actions for acts within their official duties, provided they do not involve bad faith, malicious purpose, or wanton disregard. However, election challenges, like the one faced by Wendy Link, are personal contests between candidates, not actions arising from official duties. AGO 77-87 (January 26, 1998) explicitly addresses this issue, stating that neither county funds nor the supervisor of elections’ office budget may be used to defend a supervisor in an election contest under section 102.161 F.S. The opinion clarifies that such litigation is “personal to the candidates involved” and does not serve a public purpose, as the county has no interest in the outcome of who holds office.

The two-prong test from Florida common law, established in cases like Thornber v. City of Ft. Walton Beach (568 So. 2d 914, Fla. 1990), Ellison v. Reid (397 So. 2d 352, Fla. 1st DCA 1981), and Chavez v. City of Tampa (560 So. 2d 1214, Fla. 2d DCA 1990), further reinforces this restriction. The test requires that litigation (1) arise from official duties and (2) serve a public purpose. In Thornber, reimbursement was allowed for defending a recall petition tied to official actions, satisfying both prongs. Conversely, Chavez denied reimbursement because the official’s actions served private interests, failing the public purpose prong. In Wendy Link’s case, an election challenge lawsuit fails both prongs: it does not arise from her official duties as supervisor of elections but from her status as a candidate, and it serves her personal interest in retaining office, not a public purpose.

AGO 77-87 aligns with this framework, citing Markham v. State, Department of Revenue (298 So. 2d 210, Fla. 1st DCA 1974), which ruled that public funds cannot be used for election contests, as they are “purely personal” and involve no public interest. Similarly, Peck v. Spencer (7 So. 642, Fla. 1890) and Williams v. City of Miami (42 So. 2d 582, Fla. 1949) confirm that election-related litigation is personal, not public, in nature. These rulings underscore that using taxpayer funds for such purposes is an improper expenditure.

Additionally, 36 Florida Attorney General opinions related to section 111.07 F.S. consistently restrict public fund use for defenses outside official duties or involving misconduct. For instance, AGO 80-19 (March 10, 1980) prohibits funds for a former housing authority member’s legal defense, as it served no public purpose. AGO 90-74 (September 4, 1990) notes that reimbursement for ethics charges requires a public purpose, which election contests lack. The 2017 informal opinion (November 30, 2017) further clarifies that common law exceptions apply only when actions are tied to official duties and public benefit, not personal litigation like election challenges.

Using taxpayer funds for Wendy Link’s defense would constitute official misconduct, as it misappropriates public resources for personal gain, violating the public trust. Florida law and these precedents demand that public funds serve public interests, not personal legal battles. Thus, Link’s attempt to use taxpayer funds is illegal, unsupported by legal authority, and contrary to the principles of public accountability.

Recently, Wendy Link sought to increase the Palm Beach County Supervisor of Elections litigation fund… To Support her personal legal defenses of election fraud, official misconduct, altering election records and other serious felonies related to her ongoing election fraud RICO enterprise.

Is such a dramatic increase suspicious?

Jeff Buongiorno caught Wendy Link cheating…

Link and her direct reports were caught altering election records and deleting records to conceal the fraud.

IS THIS AN ETHICS VIOLATION?

Wendy Link’s use of taxpayer funds to defend an election challenge lawsuit constitutes an ethics violation under section 112.313(6), F.S., as it misuses public position for personal benefit, contrary to law. This is supported by AGO 77-87, 36 related Attorney General opinions, and cases like Thornber, Ellison, and Chavez. The violation warrants an ethics complaint, as it involves a breach of public trust, and the Florida Commission on Ethics provides a mechanism to address such misconduct.

If you find this repugnant you can also go and file an ethics complaint against her at the following link.

https://www.ethics.state.fl.us/Documents/Forms/Complaint%20Form.PDF?cp=2024719

Attorney Accountability Under Florida Law

Attorneys are generally not liable for their client’s decisions on funding legal defenses unless they actively participate in or knowingly enable illegal actions. Potential avenues for accountability include:

Civil Liability:

An attorney could face civil liability if they conspired with the client to misappropriate public funds or knowingly accepted funds they knew were illegally obtained. Under Florida tort law, conspiracy requires an agreement to commit an unlawful act and an overt act in furtherance (see Snipes v. W. Flagler Kennel Club, Inc., 105 So. 2d 164, Fla. 1958). Without evidence that the attorney agreed to or knowingly facilitated the misuse of taxpayer funds, civil liability is unlikely.

Section 768.28, F.S., limits personal liability for state agents acting within their scope, but this does not typically extend to private attorneys. If the attorney was a public employee (e.g., county attorney), liability could arise only for bad faith or malicious actions, which is not suggested here.

Criminal Liability:

Misappropriation of public funds could implicate criminal statutes like section 838.016, F.S. (unlawful compensation for official behavior), or section 812.014, F.S. (theft). However, the attorney would need to have knowingly received or aided in the misuse of funds with criminal intent. Absent evidence of such intent, criminal liability is improbable.

Recovery of Funds:

If public funds were improperly paid to the attorney, the county could seek restitution. In City of Miami v. Benson, 63 So. 2d 916 (Fla. 1953), the court ordered repayment of improperly spent public funds, but this targeted the public official, not the attorney. The attorney might be required to return fees if they knew or should have known the funds were misappropriated, but this is a civil remedy, not direct accountability for the misuse.

Ethical Accountability

Under the Rules Regulating The Florida Bar, attorneys have ethical obligations that could trigger accountability:

Rule 4-1.5 (Fees and Costs for Legal Services): Prohibits charging or collecting illegal or clearly excessive fees. If the attorney knowingly accepted public funds for a defense prohibited by law (e.g., per AGO 77-87), this could violate the rule, especially if they failed to advise the client of the impropriety.

Rule 4-8.4 (Misconduct): An attorney commits misconduct by engaging in conduct involving dishonesty, fraud, deceit, or misrepresentation, or by knowingly assisting a client in illegal conduct. If the attorney advised or assisted Wendy Link in using taxpayer funds despite knowing it was illegal, this could constitute misconduct.

Rule 4-1.2 (Objectives and Scope of Representation): Requires attorneys to abide by a client’s lawful objectives. If the attorney pursued payment from public funds knowing it violated section 111.07 F.S. or AGO 77-87, they could face ethical scrutiny for facilitating an unlawful objective.

A bar complaint could be filed with The Florida Bar if evidence shows the attorney knowingly accepted improper funds or failed to advise against their use. Disciplinary actions could range from admonishment to suspension or disbarment, depending on the severity (section 3-5.1, Rules Regulating The Florida Bar).

Taxpayers should NOT be funding Wendy Link, Palm Beach County Supervisor of Elections legal fund!

What a mess! At least the spotlight is on Link.